What is Cognitive Load Theory, and what does it look like in action?

Cognitive Load Theory (or CLT) is a theory that aims to understand how the cognitive load produced by learning tasks can hinder students’ ability to process new information and create long-term memories. Understanding CLT can help teachers apply more effective teaching methods and enable us to recognize it in action and know how to support students when it occurs. Cognitive load can peak when the demands on a learner are too high, making the task of processing new information very complicated. When cognitive load is managed well, students can learn and retain new skills more effectively.

John Sweller, an Australian cognitive scientist, first proposed the theory in 1988 (source: Psychologist World). There are three types of cognitive load:

Intrinsic Cognitive Load – the demand posed by the quality of the information being learned.

Extraneous Cognitive Load – demands imposed by a teacher for new learning.

Germane Cognitive Load – the demands imposed by learning new skills and other information.

For further reading on Cognitive Load Theory, I suggest the following websites:

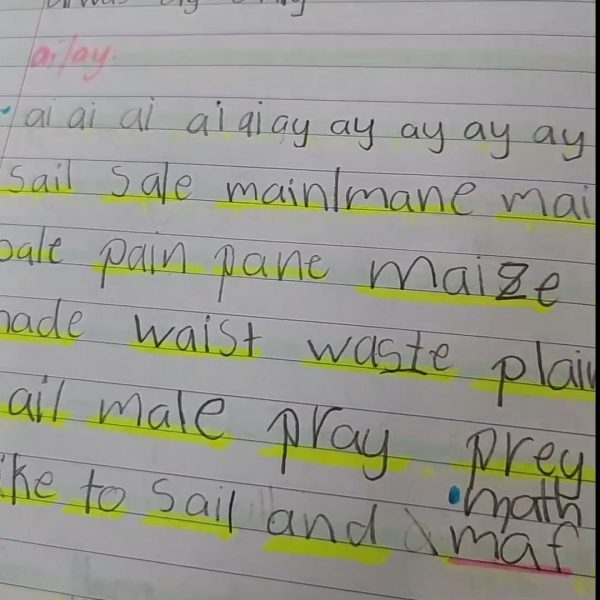

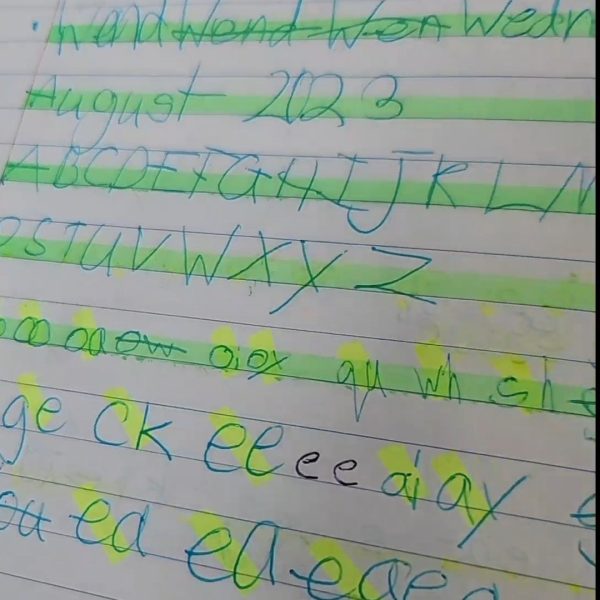

So, what does it look like in action? Recently, I noticed a student I had been working with for a long time suddenly experienced a decline in her writing and spelling abilities. She typically had neat and tidy handwriting and coped well with the introduction of new sounds and their spelling correspondences, making good progress. You can see this in the image below:

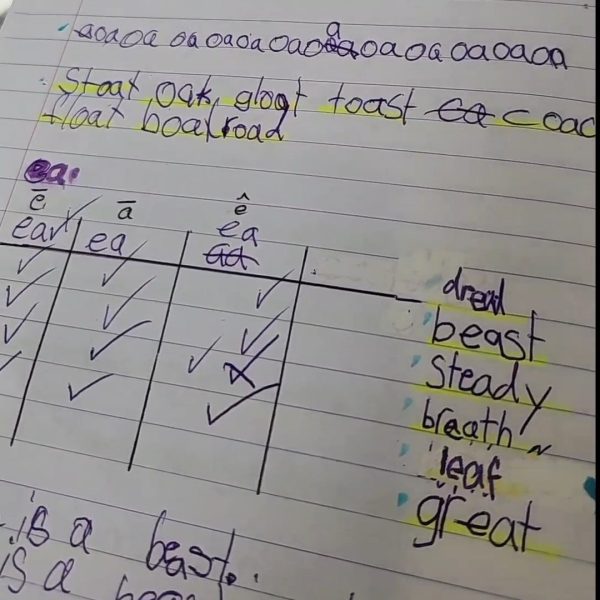

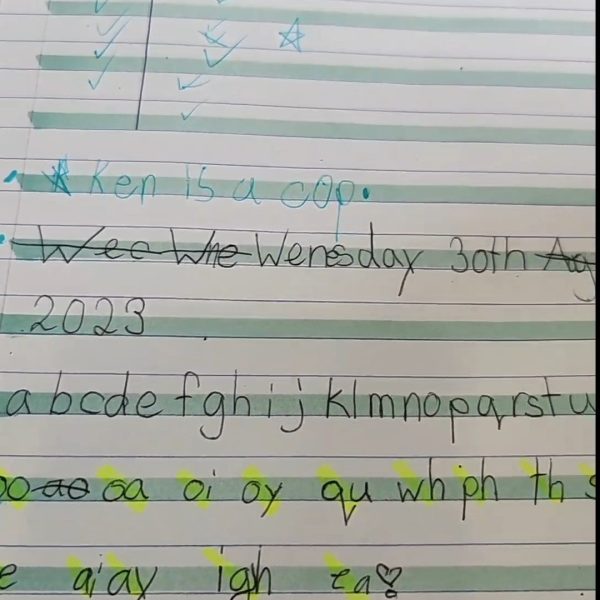

All of a sudden, however, things were not going so well. Drawing on my knowledge of cognitive load theory, I thought to myself, “Okay, obviously, I’m going too fast, or I am introducing too many concepts or sounds too closely together. It’s time for me to pare back and give her time to consolidate some of the things I’ve been teaching over the last few weeks.” This is what her work began to look like, under cognitive load:

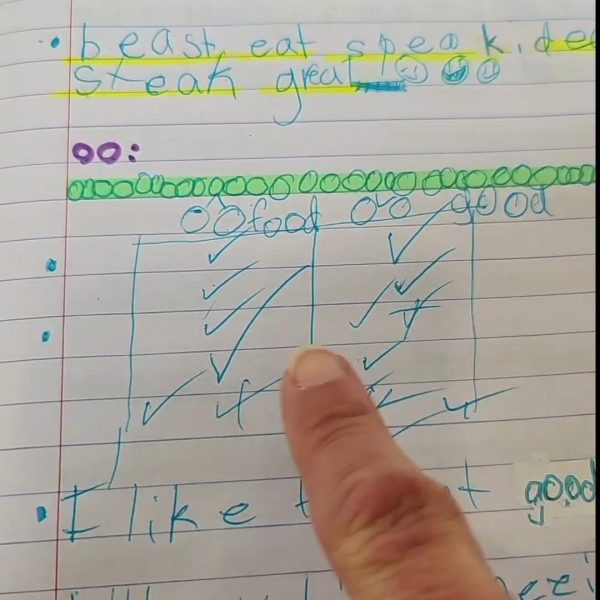

As you can see, I started introducing multiple sounds for spellings, (ea, ea, ea) and it became increasingly challenging for her to map these sounds or make sense of the sound-symbol correspondence. In the next image, my student chose not to write; she actually chose to tick instead. I had introduced oo/oo straight after ea/ea/ea. This clearly demonstrates the impact of cognitive load. I had overloaded her with too many sounds, and there was too much to think about, causing her to struggle with things she had previously mastered. This was a significant warning sign to me. In the images below, the student struggled to write the date and the uppercase alphabet and then chose to tick instead of write. This led me to abandon the lesson I had planned.

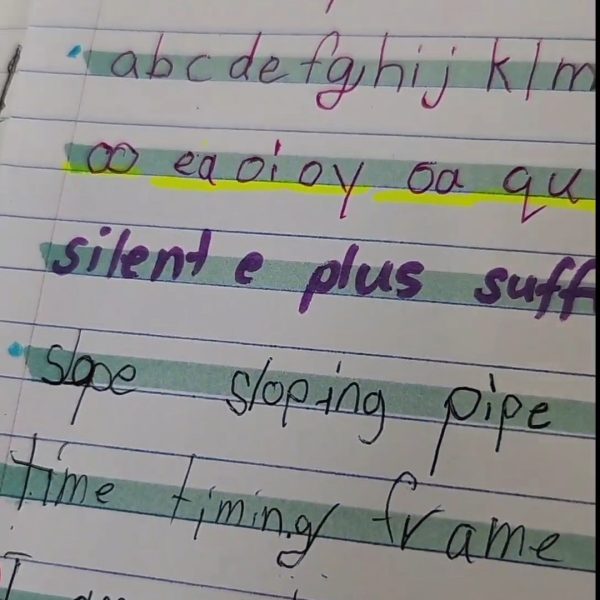

I had to consider how to teach her while maintaining her confidence in learning and experiencing success. This was crucial. The first thing I did was reintroduce scaffolded paper, which made a big difference in the size of her writing.

The next step was to revisit concepts and syllable types that she was already familiar with, such as Silent E, which we had been learning for the past year. You can see here that her writing improved significantly, her sounds were accurate, and she had grasped the concept of what to do with Silent E plus suffix. We were able to expand on sentence construction, and she excelled in expanding her sentence – she even wrote a sentence with an appositive in it.

In conclusion, it’s important to consider cognitive load theory when working with neurodiverse students on the dyslexic spectrum, possibly with dysgraphia or ADHD as well. Be vigilant in identifying signs of cognitive load, and be familiar with what it looks like in action. It’s also important to think about working memory and simplify your lessons, ensuring you are playing to your student’s strengths and helping them experience success within your lessons.