This blog post is the fourth in a series about writing. I was prompted to write these after coming across a post about writing in a forum I follow a few weekends ago. The post described a parent’s frustration with their child’s writing process. Although the child writes extensively to express their ideas, the resulting work is affected by poor spelling, lack of punctuation, and illegibility when later reviewed.

In part one, I explained that writing is far more than just putting words on a page. It’s a multifaceted skill that requires a deep understanding of language, communication, and human emotion. I wrote about how we must recognise the complexities of writing and the importance of mastering it so that learners can hone this critical skill.

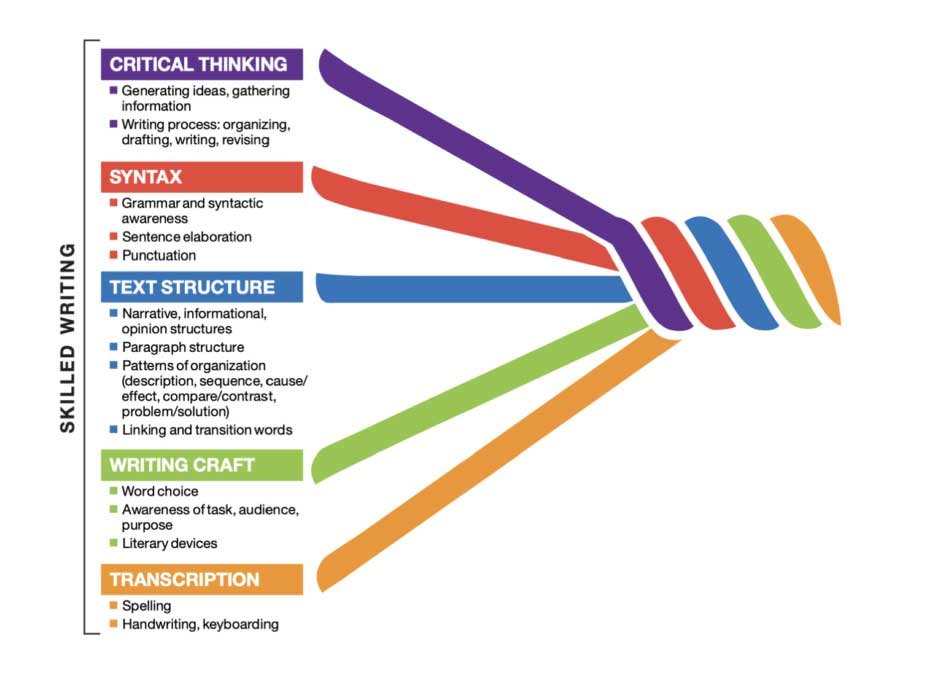

In part two, I looked at two theories behind writing, The Simple View of Writing (Berninger et al., 2002) and The Writing Rope (Sedita, 2019). Understanding the complexities of writing through frameworks like the Simple View of Writing and the Writing Rope allows us to pinpoint the specific challenges a child may face.

In part three, I deviated slightly by looking at The Simple View of Writing through a dyslexic and dysgraphic lens. I then linked this to The Writing Rope. I hoped to provide insights and knowledge so you may make informed decisions about students who need additional support with writing before it’s too late.

In this post, I will talk about the declining writing rates in New Zealand and pose some questions to consider why. I will then look at my own anecdotal data on where most gaps lie in writing with my students. We will then look at where you could start in order to build your own knowledge about teaching writing.

Sadly, the available evidence suggests New Zealand children have significant issues with writing, and unfortunately, these are getting worse over time (The Education Hub, Walls & Braid (2023)). The Education Hub report “What’s Happening with Literacy in Aotearoa New Zealand” suggests there could be education-level reasons for this (for example, a lack of systematic literacy skills and knowledge), school and teacher level explanations (for example, effective literacy pedagogy is not present within the classroom), and beyond school explanations (for example, socio-economic factors).

When we look at the education system and make links with a lack of systematically taught literacy skills, knowledge, and pedagogy, there is a distinct hangover of practice from the Balanced Literacy era.

In her book “The Knowledge Gap,” Natalie Wexler asks a pertinent question: Should children be encouraged to write at length about their own experiences and develop their “voice” without worrying much about the conventions of written language? What will go wrong if we persist with this practice?

We know that writing is made up of so much more than words on a page, and The Writing Rope framework (Sedita, 2019) showcases this:

© 2019 Joan Sedita, Keys to Literacy. Published in The Writing Rope: A Framework for Explicit Writing Instruction in All Subjects (Brookes Publishing Company).

If students are just told to ‘write with no limits or boundaries, just get the ideas out,’ are they then taught how to draw on their critical thinking skills about a writing topic, or to understand how to put sentences together to make sense, and be organised? Is each limitless idea-filled prose then corrected, and are students provided with feedback? Can they link sentences and phrases? Are these boundaryless writing exercises teaching students to be aware of their audience – who they are writing for – to convey meaning and create an effect? Are they able to spell, and is their handwriting legible, finally, is all of this done with immediate and corrective feedback?

Wexler also asks if we agree that most students will only learn to write if instruction is grounded in curriculum content, and alongside this, if we agree they are explicitly taught how to construct sentences and plan and revise paragraphs and essays. There is food for thought here, which I encourage you to explore.

The students I am lucky enough to work with come from a variety of backgrounds and levels of literacy. I work with some very (and not so very) dyslexic and dysgraphic learners, those on the ASD spectrum, along with those on the ADHD spectrum. I also work with many learners who just need to ‘catch up’. No two students are the same, and literacy levels are just as varied.

So where do you start? In my role as a tutor, I work from the ground up. First, I will carry out a series of screening tests that identify gaps in the lower level of The Writing Rope, namely handwriting and spelling. I can answer the following questions:

- Can they form their letters correctly and with automaticity?

- Can they spell with automaticity (to their current level)?

Without having automaticity in handwriting and spelling, students will find it increasingly difficult to focus on the upper levels of The Writing Rope. If there are gaps with learners, it makes sense to practice these skills every day so they become automatic. Practice means progress.

Following screening done with handwriting and spelling, I then get students to write a short text for me of their choice. Here I can begin to answer questions like:

- Do they come up with an idea to write about easily?

- Do they have enough background knowledge about something in order to write about it?

- Can they put a well-constructed sentence together with a subject and a predicate that makes sense and is correctly punctuated?

- Do they know how to chunk text into paragraphs?

- What is their word choice like? Does it match their oral vocabulary?

- Do they know who they are writing for?

More often than not, most students will struggle with coming up with an idea, fail to punctuate correctly, and have trouble with creating coherent sentences and paragraphs. The Writing Rope is an excellent framework to use to find the gaps.

When starting on my own journey, my first port of call was The Writing Revolution (TWR). The Six Principles of The Writing Revolution are based on the following (for more information read this article here):

- Students need explicit instruction in writing, beginning in the early primary school years.

- Sentences are the building blocks of all writing.

- When embedded in the content of the curriculum, writing instruction is a powerful teaching tool.

- The content of the curriculum drives the rigor of the writing activities.

- Grammar is best taught in the context of student writing.

- The two most important phases of the writing process are planning and revising.

TWR has a suggested scope and sequence they call a ‘Pacing Guide. Note you can download the Pacing Guides here.

I found this to be an excellent place to start my journey and taught for several months using the scope and sequence. I did, however, start to find that I had learners who needed to go deeper, and I myself needed to go deeper into grammar and syntax. I was just brushing the surface and for some of my very young students and those students with learning differences, they needed more explicit teaching.

My next port of call was The Syntax Project. The Syntax Project was facilitated by Stephanie Le Lievre from Serpentine Primary School (WA). Teachers and school leaders from 17 different primary schools across Australia participated, generously putting together explicit instruction-based lessons which are freely available and customisable.

The Syntax Project is underpinned by The Writing Revolution, along with some teachings from Writing Matters by William Van Cleve. The customisable slides start from Year 0/1 with oral-based lessons, moving up to the New Zealand equivalent of Year 7/8. Each slide is clear and concise and provides plenty of the I do, We do and You do framework.

As I teach across all levels, with my youngest learner currently in Year 2 and my oldest learner in Year 10, it soon became apparent to me that these lessons followed a general sequence over several years which I then adapted as a single scope and sequence I could jump in at any point depending on what my screening data showed.

Teaching writing takes on a multifaceted scope. During each lesson, we cover the following:

- Handwriting

- Spelling

- Grammar and Syntax

- Sentence-Level Writing

Where to next? I am currently going through progress assessments. We have not yet done the writing element of it; however, I am interested to see what differences in writing there have been compared to the initial assessment for new students, and over the last 6 months for existing students.

For older students, I have just started to introduce them to things like writing a good introduction, and that paragraphs can be organised to convey a specific purpose, including description, sequence, cause and effect, compare and contrast, problem and solution.

I have just started to dive more deeply into the role of background knowledge after reading The Knowledge Gap by Natalie Wexler, and I am looking at SRSD. This framework seems to work well for those with learning differences – I feel excited as to where this might take me.

In conclusion, addressing the complex and multifaceted nature of writing is crucial, especially given the declining rates in New Zealand. By understanding frameworks like The Simple View of Writing and The Writing Rope, educators can identify and address specific challenges faced by students. The importance of explicit instruction, as highlighted by The Writing Revolution and The Syntax Project, cannot be overstated. It is essential for students to develop foundational skills in handwriting and spelling before moving on to higher-order writing tasks.

As educators, we must ensure that our teaching strategies are informed by research and tailored to the individual needs of our students. Whether dealing with neurotypical learners, those with dyslexia, dysgraphia, or other learning differences, our goal should be to provide structured, explicit, and content-rich instruction that fosters not only the technical aspects of writing but also the critical thinking and creativity necessary for effective communication.

By starting with thorough assessments and progressing through a well-defined scope and sequence, we can help all students build the skills they need to become proficient writers. This journey requires patience, dedication, and a commitment to ongoing learning and adaptation. Ultimately, our efforts will enable students to express their ideas clearly and confidently, preparing them for future academic and personal success.

Further reading and articles used to write this blog post:

https://www.aft.org/ae/summer2017/hochman_wexler?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

https://nataliewexler.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TheKnowledgeGap_DiscussionGuide.pdf

https://theeducationhub.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Ed-Hub_Long-literacy-report_v2.pdf

https://thesyntaxproject2022.squarespace.com/thegrammarproject